Flatten the Program Lifecycle

02 January, 2023

This post represents a change in how I have reasoned about software and I think could be of some value to others. I am not claiming that any of the information is novel but I still don’t think it has gained full mind share.

Sidenote: I began writing this about a year ago and since then Jack Rusher has released a wonderful talk Stop Writing Dead Programs which addresses some similar concerns.

I think the traditional way we break down the Program Lifecycle is keeping us from making radical improvements in the field of Computing. The Program Lifecycle for those unfamiliar is the set of stages a program goes through in order from source to completion:

Simplified Program Lifecycle:

- Edit Time - A person types source code into an editor

- Compile Time - Source code is turned into machine code by a compiler

- Run Time - The software is executed

I’m aware there are also interpreted programming environments that aren’t compiled in a traditional sense; we’re going to circle back to that.

Dividing up the program lifecycle into these disjoint stages is limiting the design space of programming and therefore interactive computing. One area in which this program lifecycle is missing is the context in which the program is executed. The first piece of context is when the program plans to be executed. Broadly I think this can be split into two camps:

- Classical Programming (Programming for the future)

- Interactive Computation (Programming for the now)

Classical Programming

Classical programming is the domain most programmers are familiar with and that most of the tooling and theory we’ve developed are built for. This is programming with the intent of describing a computation and having it run at some later point.

This goes back to the beginning of programming when programmers would write programs by hand and then submit them in batches for a mainframe to process. Most of our programming is still done in this style.

For many domains this delay between describing a computation and the actual computing is intentional. The obvious case is still Batch Processing where some computation is intentionally scheduled or queued to run at a later time. This can both be done for resource utilization reasons (run this computation during off-peak hours) or because some later input will be available at the scheduled time (run a report at the end of the month).

A related case where it’s necessary to consider a computation deferred is the case where it’s run on a machine other than the one it was initially written on. If you plan on distributing a computation over a cluster of machines or just running it on another one as is often the case in scientific computing you have lost all the interactivity from the editing stage. You can recover some of this interactivity by transmitting data back and forth between machines but it will always be desirable to submit a computation to the external machine and not block on that operation.

Even in situations where you don’t intentionally want to defer computation you can still be forced into this situation as is the case when handling external events. If you want to write a program that can listen to a socket or receive emails, you will be programming for some event that happens after the fact; potentially when you’re away from a computer altogether.

The most interesting form of delayed computation is programming for reuse. Often when we are programming we’re not trying to calculate a single value or perform a side effect; we’re trying to write something that can be used over and over to calculate disparate values or perform differing side effects. This does not preclude you from using an interactive environment to write these reusable components but the component at the end is intended to survive past the context of the developer's interactive session. This is distinct from the previous cases in which the program could get run in a single different context from the one the programmer wrote it in; in this case, the program could get run in MULTIPLE different contexts many of which could be unknown by the initial programmer.

Lastly, I would like to suggest that even in an interactive computing context if the computation to be run has multiple components and takes a significant time to run that’s indistinguishable from a program that gets run at a later time.

Interactive Computing

There is no bright line delineation between Classical Programming and Interactive Computing. A REPL that is running an expensive function is the same case referenced above as a long-running batch job. I would like to not get hung up on this fact.

Interactive computing is any sort of computation that is intended to happen during use. More colloquially we usually say this is “using software” in contrast to “writing software”. This categorization is quite broad as it encapsulates most use today.

Some examples:

- Traditional calculator usage

- Word Processing

- Spreadsheets

- Photoshop/Image Processing Applications

- 3D modeling

- Web Browsing

- Video games

- Video playback

- REPL usage

- Jupyter Notebooks

The advantages of Interactive Computing should be obvious to anyone familiar with modern software but have also been written about at length by more knowledgeable sources than myself. If you are looking for further reading in the space I would suggest looking into the field of Human-Computer Interaction, the writings of Don Norman (especially his work into the Gulf of Execution and Gulf of Evaluation) and for inspiration, in what’s possible in the medium I suggest exploring the works of Bret Victor.

Most of the above examples probably don't seem very interesting or “programmer-esque” with the exception of the calculator, spreadsheet, notebooks, and the REPL. These are interesting because they're more straightforwardly performing similar computations to the ones we do in Classical Programming except the context is fully known and the result is wanted immediately. In the REPL/spreadsheet case, we may even want to create computations in more of the classical style but we do so in an interactive fashion.

The reason that this is still interesting from the lens of programming is that most of these constraints that we’ve imposed on the interactive computing domains are entirely artificial. Much of the software that we use in an interactive setting would benefit greatly if we had access to more powerful tools during the context of use. Imagine a world where you could perform live programmatic operations on your email inbox; for example, you could get a list of everyone who sent you an email more than a week ago for whom you haven’t responded and automatically generate a reply apologizing for the delay. Currently, these problems require software development knowledge and the use of specialized expert tools separate from the originating application.

False Dichotomies

A lot of the supposed tradeoffs that cause flame wars are really just people trying to cross this chasm.

Compiled vs Interpreted Languages

Interpreted languages are programming languages that are executed directly from source at runtime rather than going through a secondary compilation step. This is more of a classification of the runtime system rather than the language itself; a single language could be run in an interpreter or compiled into a binary. Interpretation essentially combines the compilation and runtime steps into one with some interesting consequences.

First, since compilation is skipped in interpreted language the time to begin some form of execution generally has lower latency since the interpreter doesn’t have to fully consume the program but just run instructions as they occur. This can lead to interpreted languages feeling more interactive than their compiled counterparts.

On the other hand, since compiled languages have a full compilation phase that consumes the entire program they can generally use this phase to both improve performance as well as find potential errors that the programmer may have made during edit time.

Data Exploration via notebooks

There have been many talks on the pros and cons of using programming notebooks such as Jupyter. Programming notebooks are an exploratory form of programming environment that is used for a form of live data analysis and experimentation.

This is an especially interesting case for us because these environments are using tools traditionally meant for classical programming but targeting a use case that is explicitly interactive and exploratory in nature.

One of the frequent complaints about Jupyter notebooks is the order in which code cells have been run and what data has been loaded is an implicit and hidden state of the environment. This can make it confusing for the user to understand what is going on at any moment. This doesn’t happen with classical programming tools because every time you start a program all the state is built from scratch. In non-programming applications, this happens less often because the applications are built from the ground with the goal of making state management a clear priority while exposing important states to users.

Another common complaint is that notebook-driven development does not follow traditionally good software engineering methodologies or practices. Clearly if the goal was just data exploration and short-term experimentation this wouldn’t be an issue. But by the nature of having an environment available to develop analyses that can be shared and reused, the desire for additional robustness becomes invaluable.

To be clear this is not meant to be an endorsement or admonishment of notebooks but rather to acknowledge the unfortunate tradeoffs that their potential audiences are forced to make.

What do we mean by runtime anyways?

I have been using the term runtime throughout this in the colloquial sense. It’s probably important to be more precise to avoid confusion. A runtime system or runtime environment is the collection of software resources bundled together to run a program. It’s essentially the software for a given programming language that is used to run a program. For example, this could be the JRE for java or the Python interpreter for Python.

The runtime phase of the lifecycle, which is what we generally referred to in the rest of the post, refers to the stage in which the program is actually executed. Wikipedia specifically says "in which the code is being executed on the computer's central processing unit”. Unfortunately this does not necessarily match it’s colloquial usage.

For example when someone says they like REPL driven development because it allows for them to interact with their code at runtime what they generally mean is they want the ability to interact directly with the runtime environment and execute code on the fly, not that a certain piece of code is currently being executed on the CPU.

Similarly, if we think of the following python program:

import time

if 2 == 1:

while True: # Infinite Loop

print("Stuck Forever")

time.sleep(60)This program executes an infinite loop inside a conditional that evaluates to false and then waits for a minute. In general while we “run” this program we would say it exists at runtime yet lines 4-5 are never going to be “run” and for the vast majority of the program nothing will be executing on the CPU because the program will be sleeping waiting for an interrupt from the kernel.

I would like to claim that this definition of runtime is not what people actually mean. Alternatively, you could suppose that it could mean that the code was either parsed or loaded into memory but I think these are implementation details not capturing the essence of what we mean by the phrase.

The definition that I would like to adopt is that runtime is the phase in which the language’s runtime system has access to the computation. Said another way this means that the language’s runtime system could run or interact with the code. The important distinction here is it does not matter what code if any is actually “executed” but rather that there’s some language support for the code at its current state.

Affordances

So what is the problem we actually care about?

I posit that the problem we’re trying to solve in these two contexts is good affordances. Don Norman defines affordance to be the relation between some agent and an object. In our case, the affordance we care about is the interaction between someone and their computing environment.

The current divide between programming and software usage provides different affordances for programmers and users respectively. Classical Programmer affordances for example happen at edit time since that’s the stage of the program lifecycle in which the programmer interacts with the system. User affordances however occur during the use of the system.

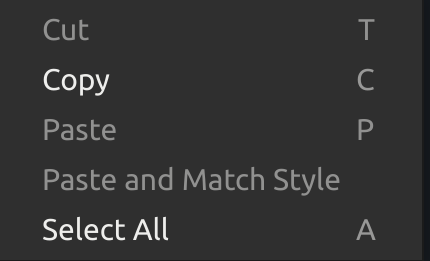

Affordances are generally quite good in end-user applications. Well-designed applications provide contextual menus that provide actions that are available given the current state and data. Additionally, they can show potential operations that are not currently possible but could be in another context (such as menu items being “greyed out”).

This context menu example is not shown as an example of great interaction design but rather how interactions with the software are better enabled when the affordances are provided making it clear what actions are possible.

Programming tools on the other hand usually have quite poor affordances. Code is usually typed into a text editor which has minimal understanding of the particular language semantics and external state is entirely unrepresented. Particularly good development environments have syntax highlighting and support refactoring capabilities but this is usually implemented completely separately from the language’s runtime duplicating a lot of the parsing and semantic understanding. Many IDEs also come bundled with debugging capabilities and methods to run the software but these are often completely orthogonal to the editing experience. You generally edit the code in a plain static text environment then iterate through the running program using a step-debugger and have separate affordances available there. Even dealing with errors during execution is quite a poor experience in most environments.

On the other hand programming tools often give you the ability to create robust solutions that are capable of solving large-scale problems as well as building tools in a way that’s usually unfeasible in “end-user” applications.

Flatten the lifecycle

(in our programming language, it's always runtime)

— Omar Rizwan (@rsnous) February 21, 2022

So now that we’ve talked a bit about both the divide of computer interaction as well as some of the unfortunate gaps, let’s turn to what we can do about it. I believe that flattening the program lifecycle is the ultimate design solution that’s necessary to resolve these issues.

What do I mean by flattening the program lifecycle?

As we said earlier the simplified program lifecycle consists of:

- Edit Time

- Compile Time

- Run Time

Flattening the lifecycle means there would be one stage that consists of all 3 of these components. What this looks like in practice is utilizing the language runtime to provide better interactions when programming.

This should not be very surprising as Language Servers have become dominant in recent years drastically increasing the effectiveness of IDEs by providing language-specific editing functionality to traditional editors. Unfortunately due to historical reasons these language servers are not generally part of the runtime but are a separate utility with much of the runtime/compiler logic duplicated. If we were to instead design our languages with this goal in mind the compiler, language server, and runtime should unify.

The natural consequence of this is your code being managed by the runtime rather than static files on a filesystem. This allows for program transformations without the need for the runtime to reparse all of the files and reinterpret the contents. Today with REPL-driven environments the REPL has the state of some code that has been evaluated but this can be different than the current state of the editor. So the programmer has to do some effort in making sure they’re reasoning about both of these states correctly. If the runtime were in charge of the code’s persistence then we could edit code with interactions of the runtime and there would be no way to have this dissonance. Calling back to our Jupyter example there are also certain application states that are difficult to represent in textual sources, such as images, large data frames, or databases; these would be much easier to store inside of an application runtime.

This is in no way an original idea and has been referred to before as Interactive Programming, a paradigm embodied by the Smalltalk system. This technique hasn’t had a big enough influence on most mass-market programming languages today. I think we’re primed for an interactive programming renaissance so I would like to put forward some possible benefits that it could bring.

Interactive computing becomes a much more interesting experience when utilizing a language built for Interactive Programming. The user interface could be adapted to particular problem domains like most traditional applications yet you’d still have access to all of the rich semantics expected in a programming language. Very much in the spirit of older Smalltalk systems Glamorous Toolkit has been making progress in this space.

We can also finally realize our dream of having stronger context-aware affordances for our computing. In an interactive session, failures could manifest themselves as messages to the user. On the other hand, if they were defining a reusable component the runtime could utilize static analysis to manifest the potential for errors during editing rather than waiting for them to fail during the context of use. Right now our tools are making us choose a side of the interactive/programming chasm and I think this will help us bridge the gap.

We talked about program transformation earlier. One criticism of automated program refactoring tools in traditional IDEs is they are usually computationally expensive and have high latency since it requires parsing and writing an entirety of a codebase out to disk. In an interactive system refactoring would be much quicker since actions would be on an already parsed AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) and would not require an explicit parse/serialization step. More importantly, though these refactors could often be performed asynchronously essentially solving the latency issue since a user could perform a refactor and keep interacting with the system while the runtime changed affected code in the background. This isn’t possible in today’s systems since the codebase needs to be in an atomic state between refactors but an interactive runtime could have multiple copies of the AST at once. This is much closer to how end-user applications have been developed for years; when performing an update we don’t serialize the entire application state to disk but rather issue an update to some database changing the necessary state.

One major concern of compiled programming environments is the lack of interactivity due to compile times. Compilation can be a notoriously slow experience. Fortunately for interactive systems, since the editing is happening through runtime interactions the codebase never needs to be fully recompiled during programming. The only code that needs to be recompiled is whatever was affected by the most recent editor interaction. Most of the time this would be adding a new expression or modifying an existing one. Adding a new expression is obviously easy to compile efficiently. Compiling an existing expression and downstream dependencies is also much easier since the runtime has access to the full dependency tree without having to scan the source code.

Another example of the type of power that’s available with a fully interactive programming system is the ability to provide more interfaces for programming. If programs were stored by the runtime and not by a textual representation they can easily be internationalized increasing accessibility to many more demographics. You could imagine having the same type of support for internationalization in your programming language that people expect from commercial software. Unison has a very interesting runtime that stores code by the hash of its AST which separates naming from the code completely allowing both seamless renaming as well as internationalization trivially.

Language extension is another pain point of current programming languages. Language designers have to be very careful when adding new features to a language not just because of the potential semantic implications but also because of the potential implications for overlapping syntax as well as readability. If the runtime handled code persistence it could also handle modifying the code when upgrading language versions. Even semantic changes to the language could often include migrations to adapt existing code.

These are just a few ideas that become possible when we start programming in a more interactive manner. I’m hoping that we see an uptick in these Programming Systems in the near future as we’re seeing an increased demand for developer tooling as well as a huge increase in the number of people interfacing with these tools.

I plan on releasing follow-up posts in the future addressing more possibilities in the future of programming systems.